Twin Spin: 17 Shakespeare Sonnets Radically Translated and Back-Translated » książka

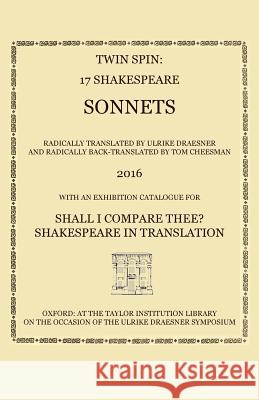

Twin Spin: 17 Shakespeare Sonnets Radically Translated and Back-Translated

ISBN-13: 9780995456402 / Angielski / Miękka / 2016 / 42 str.

Shakespeare's Sonnets have captured the imagination of German poetry translators for centuries, each of them interpreting them anew. None of these poems have been accessible in English until now. Ulrike Draesner's "radical translation," 'Twin Spin', entwines the languages of poetic reproduction and cloning. Tom Cheesman's back-translation, 'Thymine', back-translates her work into English, completing a cycle of re-interpretation. Ulrike Draesner wrote in 'Dolly and Will' (2000) about her approach: "Shakespeare's sonnets deal with procreation - manically, obsessively, directly. ...] Set against a keen sense of mortality, Shakespeare's poems are dreams of survival - both in the flesh and in writing, the two prime means of self-reproduction through the creation of memory. The sonnets fantasize marriages; 'procreate, procreate, reproduce yourself, ' their obsessive dream whispers. The interplay of gender roles goes so far and becomes so quick that the sexual determination of those involved more or less cancels itself out. Only one thing counts: to give temporality the slip (for oneself and perhaps for another, or for another and thus certainly for oneself). 'Time' is the real third party, the 'uncanny other'. It is confronted by Shakespeare with his poems' unconditional and shameless appetite for life - if there was ever anything scandalous about these poems, then it is this hunger: scandalous, intoxicating and wonderful. ...] In my radical translation, Shakespeare's sonnets thus mutate into a sequence of a clone being spoken to, of the clone responding, of the speech of clones in a cloned world. ...] My radical translations turn Shakespeare's words around, deliberately picking up on the wrong (i.e. non-canonical) ends of their polysemanticity, standing them on their heads - just as the "natural" world of reproduction is stood on its head by the possibilities of cloning. ...] In Tom Cheesman's poetic back-translations or 're-versions', "Ulrike Draesner's tricksily demotic 'Twin Spin' is] brilliantly brought to life" in English (Karen Leeder). Far from cloning Draesner's poems, he re-spins her 'Will'-ful spin on the Sonnets as more than 'second life on second head' (68). The two versions are combined with reproductions of the first edition of the sonnets in the Bodleian's copy of 'Shake-speares sonnets Neuer before Imprinted' from 1609 in the 1905 facsimile version by Lee. Together, these three versions of the sonnets, spun through languages and centuries, are published in pamphlet form on a triple occasion: the Ulrike Draesner Symposium 9-11 April 2016, the 'Shall I compare thee?' exhibition of sonnet translations in the Taylor Institution Library and the #sonnet2016 project of the Bodleian Library. The text also contains a catalogue of the exhibition. More information can be found under http: //blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/

Shakespeare's Sonnets have captured the imagination of German poetry translators for centuries, each of them interpreting them anew. None of these poems have been accessible in English until now. Ulrike Draesner's "radical translation", ‘Twin Spin’, entwines the languages of poetic reproduction and cloning. Tom Cheesman’s back-translation, 'Thymine', back-translates her work into English, completing a cycle of re-interpretation.Ulrike Draesner wrote in ‘Dolly and Will’ (2000) about her approach: "Shakespeare’s sonnets deal with procreation – manically, obsessively, directly. [...] Set against a keen sense of mortality, Shakespeare’s poems are dreams of survival – both in the flesh and in writing, the two prime means of self-reproduction through the creation of memory. The sonnets fantasize marriages; ‘procreate, procreate, reproduce yourself,’ their obsessive dream whispers. The interplay of gender roles goes so far and becomes so quick that the sexual determination of those involved more or less cancels itself out. Only one thing counts: to give temporality the slip (for oneself and perhaps for another, or for another and thus certainly for oneself). ‘Time’ is the real third party, the ‘uncanny other’. It is confronted by Shakespeare with his poems’ unconditional and shameless appetite for life – if there was ever anything scandalous about these poems, then it is this hunger: scandalous, intoxicating and wonderful. [...] In my radical translation, Shakespeare’s sonnets thus mutate into a sequence of a clone being spoken to, of the clone responding, of the speech of clones in a cloned world. [...] My radical translations turn Shakespeare’s words around, deliberately picking up on the wrong (i.e. non-canonical) ends of their polysemanticity, standing them on their heads – just as the “natural” world of reproduction is stood on its head by the possibilities of cloning. [...]In Tom Cheesman’s poetic back-translations or ‘re-versions’, "Ulrike Draesner’s tricksily demotic ‘Twin Spin’ [is] brilliantly brought to life" in English (Karen Leeder). Far from cloning Draesner’s poems, he re-spins her ‘Will’-ful spin on the Sonnets as more than ‘second life on second head’ (68).The two versions are combined with reproductions of the first edition of the sonnets in the Bodleian's copy of 'Shake-speares sonnets Neuer before Imprinted' from 1609 in the 1905 facsimile version by Lee. Together, these three versions of the sonnets, spun through languages and centuries, are published in pamphlet form on a triple occasion: the Ulrike Draesner Symposium 9-11 April 2016, the 'Shall I compare thee?' exhibition of sonnet translations in the Taylor Institution Library and the #sonnet2016 project of the Bodleian Library. The text also contains a catalogue of the exhibition. More information can be found under http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/