Fly-ku! » książka

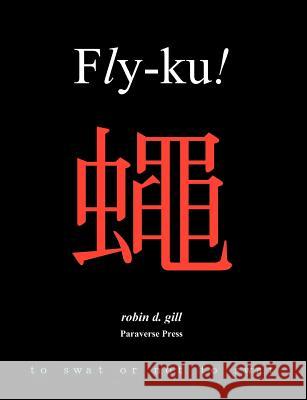

Fly-ku!

ISBN-13: 9780974261843 / Angielski / Miękka / 2004 / 232 str.

One of a line of books of translated haiku (from Japanese) about single themes by Robin D. Gill. Fly-ku introduces hundreds of haiku about flies, fly-swatters and fly-paper, scores of which are by Issa (1763-1827), whose famous ku about a fly begging not to be swatted has long been controversial because of its alleged maudlinity and anthropomorphism. Gill defends Issa and his famous fly-ku, while showing that Issa-lovers, on their part, are wrong to assume he was the first to notice flies rubbing their limbs together. There already was a century of such flies in haiku and an even older tradition of expressive "hands" in bracken that is given a whole chapter in this book otherwise dedicated exclusively to musca maledicta (and, occasionally, benedicta). Similarly to Gill's earlier Rise, Ye Sea Slugs most of the poems included are hundreds of years old and thematically chaptered, but the approach is phenomenological rather than metamorphic: flies that beg, flies that are swatted, flies that escape, flies that stay, etc.. To balance the picture, there is a long chapter with 100 modern and contemporary fly-ku, and part of the longest chapter (Sundry Flies) introduces a dozen or two foreign (English language) fly-ku. Gill, himself, professes more interest in the poetry of mosquitoes, fleas, silverfish, cicada and lightning bugs, but making a big (and totally accidental) discovery about Issa's famous fly-ku - it would seem to borrow from an unknown senryu about the warrior Benkei - he decided to do this book first. In addition to the original Japanese to all poems, there is an essay in Japanese about this discovery and its significance appended. It adds a bit to the price, but like all Paraverse Press books, Fly-ku is extremely cheap for an English language book including Japanese. A sample paragraph from the Foreword: To swat or not to swat: that is the question posed by many if not most of the thousands of haiku written about flies over the past four or five hundred years. The answer, if there is an answer, is not simple. Most Japanese poets hardly shared John Muir's sense of kinship for "our horizontal brothers," who "make all dead flesh fly," much less John Clare's gushy affection for "our fairy familiars." Even the haiku of the most merciful poet of all, Kobayashi Issa, whose feeling for flies comes closest to that of the American naturalist and English nature poet, did not really condemn swatting as most of his Western and, for that matter, Japanese readers, usually imagine."