The Popes and Britain: A History of Rule, Rupture and Reconciliation » książka

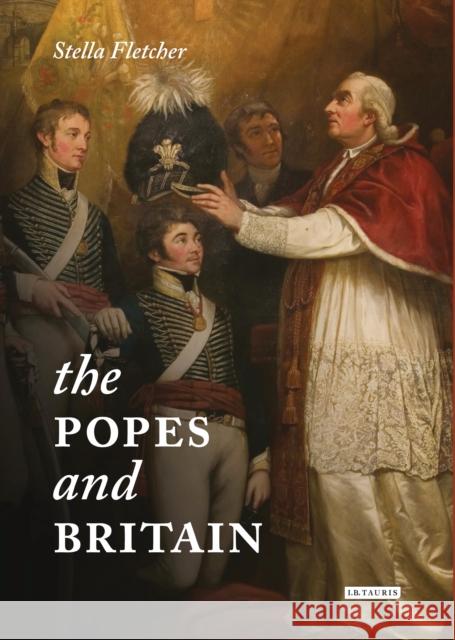

The Popes and Britain: A History of Rule, Rupture and Reconciliation

ISBN-13: 9781784534936 / Angielski / Twarda / 2017 / 264 str.

When the British thought of themselves as a Protestant nation their natural enemy was the pope. Rome's perspective was always considerably wider and the popes' view of Britain was almost invariably positive. No Christians were as devoted to St. Peter and his successors as the Anglo-Saxons who made their pilgrimages to Rome and supported the papacy by means of Peter's Pence. In the high medieval period, popes suffered opposition and attempted deposition at the hands of emperors, but England's King John placed his kingdom under papal overlordship, compounding his villainy in Protestant eyes. For its part, the Church in Scotland was recognized by the popes as a "special daughter" of the Holy See. When both kingdoms broke with Rome in the sixteenth century it was something of a sideshow in comparison with Spain's political dominance in the Italian peninsula. Thereafter, assertions of French nationalism at Rome's expense made England and Scotland appear as useful potential allies against Europe's strongest state. This was confirmed when eighteenth-century Britain emerged as a major power and its kings acquired Catholic subjects around the globe. Nothing caused a greater convergence of interests than the French Revolutionary wars and the contempt with which successive popes were treated by Britain's French enemies. Steadily overlapping interests required increasingly formal dialogue. For generations there were contacts at the elite level, much to the disgust of Britain's middle class Protestants, with diplomatic relations being formalized in the twentieth century, before the pastoral visit of John Paul II in 1982 and the state visit of Benedict XVI in 2010. As the twenty-first-century papacy looks ever more firmly beyond Europe, this new history examines political, diplomatic, and cultural relations between the popes and Britain from their vague origins to the present day, with particular emphasis on the contributions of individual pontiffs.