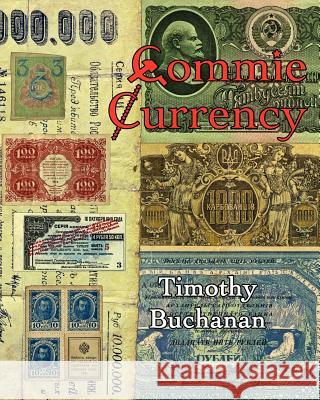

Commie Currency: : the abuse of money in the Soviet Union » książka

Commie Currency: : the abuse of money in the Soviet Union

ISBN-13: 9780983174912 / Angielski / Miękka / 2011 / 160 str.

In Karl Marx's utopian vision, there were to be no prices on products. All goods would be freely distributed; money would not exist, for there would be no need for it under communism. However, in the first nation that attempted to build a Marxist society, matters evolved quite differently. Commie Currency examines more than ninety examples of paper currency from Russia and the member states of the Soviet Union, from 1909 to 1999. Twentieth-century imperial Russia was much stronger economically that later accounts would have it. She was able to raise capital for national development from the international community, thanks to her adoption of the gold standard in 1897. But the deprivations of the Great War, coupled with economic estrangement and poor political management, led to the downfall of the Romanov dynasty. The Provisional Government that replaced the tsar might have evolved into a lasting constitutional democracy, but again, bad decisions led to the Bolshevik coup of November 1917. At first, Lenin's attitude towards money was one of simple expediency; he took what he needed. The Bolsheviks soon realized, however, that pecuniary abuse could be a tool of class warfare. During the Civil War, the belligerents each created alternative forms of payment; in this period, more different types of currency circulated than anywhere else at any time. The war created a money melee. Meanwhile, the Soviets replaced banknotes with tokens, temporary measures on the fast track to abolishing money altogether. But instead of the millennium, they brought hyperinflation and near-ruination, and were saved only by allowing a partial return to the marketplace-NEP. They then attempted an odd experiment in bipaper, with good money for the state and bad paper for the masses. Finally, in 1924, the Bolsheviks decided that the money-free society, like the World Revolution, would be a long time in coming, and they stabilized the ruble. Under Stalin and his successors, the Plan ruled; money was created as needed to fulfill targets and balance accounts. Moscow dealt with what was called the currency overhang by periodically imposing thinly disguised confiscations-in 1947, 1961, and 1991, on the eve of the collapse of communism. The book's afterword argues that money played a crucial role in that collapse, as well as provoking the conditions that pushed Soviet leaders to attempt market reforms. Marxists hate money because they see it as the method of extracting profit from the labor of others. For them, money is theft. In contrast, Ludwig von Mises and other Austrian economists have demonstrated that the free market is the only means of performing rational economic calculations. For them, money is information. Interference with the market degrades the information; this conclusion has implications for America's finances. The banknotes, tokens, securities, and vouchers are drawn from the collection held by The Museum of Orthodoxy on Colorado Springs. They are presented here in full color and, with few exceptions, at full size. Their images, symbols, and nomenclature are fully explained, and each bill is placed within its historical context. This is a book for collectors and those who love history."