The War & The Boy » książka

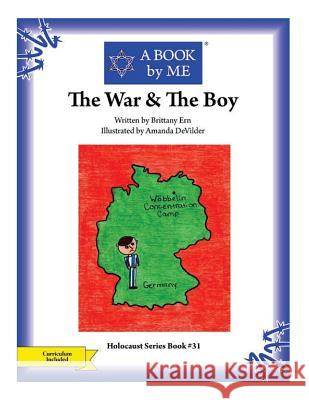

The War & The Boy

ISBN-13: 9781512255034 / Angielski / Miękka / 2011 / 26 str.

My name is Roy Kouski. As a young boy, I joined the Boy Scouts and later played high school football. Little did I know how that would prepare me for my life as an American soldier. I joined the army late in World War II. After basic training, I boarded a troop ship and took the same route to Liverpool that my dad had taken as a young soldier when he was sent overseas. I eventually got to France, where I became an infantry replacement, which meant I took the place of someone who had been injured or killed. When volunteers were requested to serve with the 82nd Airborne, no one came forward. Later, the officer read a list of names of younger men and announced that we had volunteered. I was a strapping young man, a former football player, six feet tall and 180 pounds. After being moved to Cologne, Germany, I found out how the airborne handles their dangerous missions. At reveille, the captain would announce the mission and ask for volunteers. No one blinked an eye. Then he said, "Sergeants, pick your men." In a few seconds the lottery was picked, and I became a squad leader to take men across the Elbe EL-buh] River on night patrol. A patrol had gone out each night, but they were killed. The chances of survival were not good. It was drilled into us, however, not to show cowardice in the face of the enemy. The older combat men came around with offers of equipment and advice. The chaplain came by and said a prayer. We spent the rest of the afternoon in briefings and getting instructions regarding the boat. That night, when we were getting ready for the dangerous patrol, Rangers came by to tell us they had gone across the river and had returned without being shot at. The German soldiers thought we had given up on crossing the river. We crossed successfully and headed for Berlin. The Russians had liberated a group of American GI's, and they also arrived. Then a platoon of 25 or 30 prisoners in brown uniforms, maybe Hungarians, came too. When their officer reached me, he stopped the soldiers and formally surrendered them to me, a buck private Later, we liberated the Wobbelin concentration camp. It was more of a work camp than a death camp, but the inmates were worked until they died. New people would come in, so there were always enough people to man the factory at the nearby city of Ludwigslust. The prisoners wore striped suits. They were marched into town for work in the morning and returned to the camp at night. They lived in terrible conditions and had no sanitation. They were emaciated and full of lice. They lived in narrow houses with bunks like shelves on each side. The bunks were about five or six feet wide, and three or four bunks high. When someone died, they carried him out and piled the bodies outside. The weaker ones could not compete for food, so they wasted away. We received orders to gather the "striped-suit people" to send them to a displaced persons camp to be helped. They didn't trust us. I found a young boy named Paul around 12 years old who could speak several languages. He said he would help me gather everyone if I would not make him go. I said I would. He talked many into coming with us. When it was time to leave, I told him to get on the truck too. I will never forget the hate in his eyes when I gave him orders. I probably saved his life. Paul was a Jewish survivor, and I often think I should try to find him to explain why I broke my promise. We gathered all the German civilians in town, so they could give a proper and reverent burial to the 200 dead victims found in the camp. The civilians dug 200 graves in front of their government building. Men and women of all ages carried the bodies through the streets and filled in the graves. Crosses or Stars of David were placed at each grave. After the war, I married and raised a family in Port Byron, Illinois. As I sat in my home, along the mighty Mississippi River, I thought often of Paul and wished I could apologize for breaking my promise."

Zawartość książki może nie spełniać oczekiwań – reklamacje nie obejmują treści, która mogła nie być redakcyjnie ani merytorycznie opracowana.