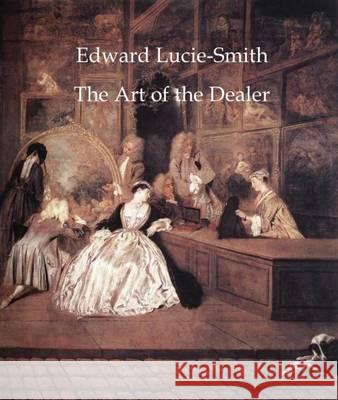

The Art of the Dealer: 2015 » książka

The Art of the Dealer: 2015

ISBN-13: 9781910110287 / Angielski / Miękka / 2023 / 150 str.

A history of the development of the art market spanning the 17th century to contemporary art today.In modern times the profession of the dealer had its start in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth centuries and was essentially due to the revolution brought about by the invention of the printing press. Prints could be offered as readymade images to a widespread market. Durer said he made more money out of his prints, more easily than he did from his commissioned paintings. His mother was his dealer, offering them in the marketplace at Nuremberg.With the rise and expansion of mercantile capitalism the sale of readymade works, supplied by third parties, not directly commissioned from the artist himself nor directly specified by the ultimate client, became a more and more common form of trading in art. This was particularly the pattern in the Low Countries and it also helped to sustain the increasingly large community of foreign artists, Netherlandish and German, who made their way to Italy, where they had no immediate social connections and needed intermediaries in order to make a livelihood. These intermediaries undoubtedly encouraged artists to tackle subject matter they believed would sell.By the early 18th century the profession of art dealer was well-established, in opposition to the official academies. Watteau's painting L'Enseigne de Gersaint portrays an upmarket Parisian establishment of this type. It is perhaps no accident that it shows a portrait of the reigning French monarch, Louis XV, being unceremoniously packed away in a box. Emblems of power now counted for less that symbols of luxury. A large mirror propped up on the right suggests that little distinction needed to be made, in this context, between paintings and looking glasses. Both were furnishings, the essential trappings of a civilized life-style, and both served to display not only their possessors' taste, but also their wealth. The big mirror, in fact, may have been more valuable than any of the paintings crowding the walls.The French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars that followed it saw a radical redistribution of art works. Naturally dealers played a large part in this - also in defining what was prestigious, therefore saleable, and what was not. In the Victorian period in London, as attention swung towards then contemporary creations, dealers such as the still surviving Fine Art Society (founded in 1877) played a major role in shaping taste. The history of this gallery in Bond Street and that of the late 19th century Aesthetic Movement are closely intertwined.In late 19th century, dealers such as Durand-Ruel (in this case through his support of the Impressionists) were increasingly important in changing the currents of taste. In Durand-Ruel's case, his influence became international. This went hand in hand with a different kind of international influence, exercised by the great British dealer Lord Duveen, In alliance with the art historian Bernard Berenson, Duveen devised a way of selling Old Master paintings, often of religious or esoteric mythological subjects, to a clientele who had little natural liking for that kind of subject-matter, by emphasizing the formal qualities of these works, rather than what they portrayed. This was a first step towards the acceptance of abstraction in art.As the Modern Movement progressed dealers such as Vollard and Paul Guilluame had a greater and greater say in defining what was important in contemporary art and what was not. This influence continued as the centre of avant-garde activity moved from Paris to New York. Galleries such as that of Pierre Matisse and Peggy Gugenheim's Art of This Century Gallery pioneered the way to the acceptance of new forms of artistic expression. Later, Leo Castelli, an immigrant from the cosmopolitan Italian city of Trieste, was instrumental in establishing the reputations of Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein. Castelli's 1962 solo show for Lichtenstein was a major step in the wor