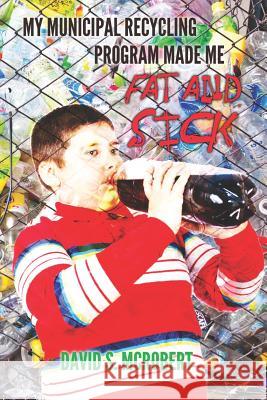

My Municipal Recycling Program made me fat and sick: How well intentioned environmentalists teamed up with the soft drink industry to promote obesity » książka

My Municipal Recycling Program made me fat and sick: How well intentioned environmentalists teamed up with the soft drink industry to promote obesity

ISBN-13: 9781470127466 / Angielski / Miękka / 2012 / 258 str.

My Municipal Recycling Program made me fat and sick: How well intentioned environmentalists teamed up with the soft drink industry to promote obesity

ISBN-13: 9781470127466 / Angielski / Miękka / 2012 / 258 str.

(netto: 76,15 VAT: 5%)

Najniższa cena z 30 dni: 80,18

ok. 16-18 dni roboczych

Bez gwarancji dostawy przed świętami

Darmowa dostawa!

This book explains the rapid evolution of the Blue Box municipal recycling program in Ontario between 1982 and 1994 and its social and environmental costs. The origins of the Blue Box municipal recycling program in Ontario can partly be traced back to the early 1970s when concerns about litter problems were attracting the public's attention. In 1976, a law under the Environmental Protection Act was passed allowing the Ontario government to enact regulations banning non-refillable soft drink containers. However, the regulations banning non-refillables cans and new plastic PET bottles were never passed and instead in 1978 the soft drink industry convinced the Minister of the Environment to sign a "voluntary agreement" that soft drink companies and retailers would sell 75 percent of its soft drinks in refillable containers. The 75 percent ratio for glass refillable soft drink containers was never reached though because the soft drink industry had trouble with the targets. The large pop producers and grocery retailers also had substantial connections to the Ontario Progressive Conservatives and made large annual donations to both the Liberals and the Progressive Conservative parties throughout the 1970s and the 1980s. In the early 1980s, environmentalists renewed their push to get the Ontario government to enforce the 75 percent "gentlemen's agreement" on refillables. At the same time, the soft drink industry contended that consumers preferred disposables such as cans and plastic bottles. What the soft drink industry really wanted was "packaging freedom": in other words, freedom to use cheaper packages for their products, freedom to concentrate ownership in their industry, freedom to eliminate the independent bottlers, freedom to increase profits and freedom to start challenging the role of unionized bottling workers. In contrast, steel workers were arguing in favour of greater use of cans to provide a more secure footing for the steel industry. Meanwhile the aluminum producers and the canning industry wanted to develop new highly mechanized production lines that made full use of aluminum and would cut labour costs for the soft drink companies. The plastics industry wanted access to markets to sell plastic bottles to consumers and the independent bottlers said they wanted a better refillable system. To resolve conflicts between these interests, a multi-stakeholder consultation process was established by the Ontario government in 1985, chaired by Professor Paul Emond of Osgoode Hall Law School. In this case, the former executive director of Pollution Probe, Colin Isaacs agreed to represent environmentalists. Isaacs decided that he would accept the concept of packaging freedom and greater reliance on plastic bottles and aluminum cans in return for greater support for recycling. Groups like Pollution Probe had been advocating recycling of newsprint, metal and glass for several years and using more valuable materials like aluminum to subsidize curbside recycling seemed like a way to break the barriers that had been encountered. With Pollution Probe's support, participants involved in the multi-stakeholder consultation agreed to relax the refillable quota to 40 percent, that is, down from 75 percent, if the soft drink industry contributed $1 million to help set up Ontario Multi-Material Recycling Inc. or OMMRI and develop a Blue Box system (BBS). Eventually the amount of the contribution was increased to $20 million. The consequences of this policy choice have been environmentally, socially and economically significant and have helped to spur a massive increase in the rate of soft drink consumption in Ontario, and a related increased in obesity among many adults and youths who consume sugar-laden soft drinks at a staggering rate. The book also explores how Ontario's BBS increased green house gas production related to aluminum production and energy consumption related to long-distance shipping.

Zawartość książki może nie spełniać oczekiwań – reklamacje nie obejmują treści, która mogła nie być redakcyjnie ani merytorycznie opracowana.