My Larger Education: Being Chapters From My Experience » książka

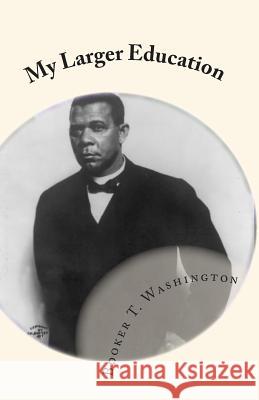

My Larger Education: Being Chapters From My Experience

ISBN-13: 9781450593052 / Angielski / Miękka / 2010 / 358 str.

My Larger Education: Being Chapters From My Experience

ISBN-13: 9781450593052 / Angielski / Miękka / 2010 / 358 str.

(netto: 78,50 VAT: 5%)

Najniższa cena z 30 dni: 78,68

ok. 16-18 dni roboczych.

Darmowa dostawa!

IT HAS been my fortune to be associated all my life with a problem a hard, perplexing, but important problem. There was a time when I looked upon this fact as a great misfortune. It seemed to me a great hardship that I was born poor, and it seemed an even greater hardship that I should have been born a Negro. I did not like to admit, even to myself, that I felt this way about the matter, because it seemed to me an indication of weakness and cowardice for any man to complain about the condition he was born to. Later I came to the conclusion that it was not only weak and cowardly, but that it was a mistake to think of the matter in the way in which I had done. I came to see that, along with his disadvantages, the Negro in America had some advantages, and I made up my mind that opportunities that had been denied him from without could be more than made up by greater concentration and power within. Perhaps I can illustrate what I mean by a fact I learned while I was in school. I recall my teacher's explaining to the class one day how it was that steam or any other form of energy, if allowed to escape and dissipate itself, loses its value as a motive power. Energy must be confined; steam must be locked in a boiler in order to generate power. The same thing seems to have been true in the case of the Negro. Where the Negro has met with discriminations and with difficulties because of his race, he has invariably tended to get up more steam. When this steam has been rightly directed and controlled, it has become a great force in the upbuilding of the race. If, on the contrary, it merely spent itself in fruitless agitation and hot air, no good has come of it. Paradoxical as it may seem, the difficulties that the Negro has met since emancipation have, in my opinion, not always, but on the whole, helped him more than they have hindered him. For example, I think the progress

Zawartość książki może nie spełniać oczekiwań – reklamacje nie obejmują treści, która mogła nie być redakcyjnie ani merytorycznie opracowana.