Hard Men Humble » książka

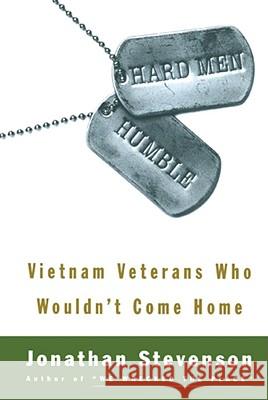

Hard Men Humble

ISBN-13: 9781416576273 / Angielski / Miękka / 2007 / 244 str.

It is finally time to come to terms with a generation of underappreciated, now middle-aged men: America's Vietnam veterans. In many ways they were no different from the men who left for Europe in 1917, or for Asia and Europe in 1942. They were young, freshly trained, scared yet determined soldiers. In Hard Men Humble, Jonathan Stevenson introduces us to a fascinating community of expatriate Vietnam veterans -- the men who wouldn't or couldn't leave Southeast Asia, and could not leave behind the people they had fought and defended. Some were military heroes and remain unalloyed patriots. Some questioned or condemned the war and find their patriotism forever compromised by it. Some stayed behind in order to relive the best part of the war with girls, golf, and Singha beer at smoky saloons. Others were moved to atone for the war with charity -- educating Thai children, building hospitals for the Vietnamese, or providing medical care to Laotians they had befriended when soldiers. Whatever each man's motivation, the one attribute virtually all expat vets share is the desire to do what so many Americans don't want them to do: remember the Vietnam War.

Hard Men Humble brings a vivid cast of characters to life: Major Mark Smith, a much bemedaled winner of the Distinguished Service Cross and former prisoner of war who works out of Bangkok relentlessly searching for MIAs; Ken Richter, once a Jersey City tough, who discovered discipline and honor in Special Forces and who now donates much of his earnings to Southeast Asian charities; Robert Taylor, a former Green Beret from Alaska who formed a bond with a Lao tribe with which he worked, and who founded a medical charity for them; and Greg Kleven, an Oakland-born Force Recon marine who lost faith in the war and in his country, descended into dissoluteness and self-destructive drinking, and believes that moving to Ho Chi Minh City saved his life. The expatriate Vietnam veterans are, ultimately, just like any other cross section of Americans: some are heroes, a few are knaves, and others are just ordinary men trying to make a living. Ironically, the very dismissal of Vietnam veterans in the United States has driven some of them to build a life abroad of greater imagination, adventure, benevolence, and fulfillment than they might have found at home. Whether or not Americans doubt the wisdom of their larger historical mission, Vietnam veterans risked their lives to serve their country. We owe them our gratitude.It is finally time to come to terms with a generation of underappreciated, now middle-aged men: Americas Vietnam veterans. In many ways they were no different from the men who left for Europe in 1917, or for Asia and Europe in 1942. They were young, freshly trained, scared yet determined soldiers. In Hard Men Humble, Jonathan Stevenson introduces us to a fascinating community of expatriate Vietnam veterans -- the men who wouldnt or couldnt leave Southeast Asia, and could not leave behind the people they had fought and defended. Some were military heroes and remain unalloyed patriots. Some questioned or condemned the war and find their patriotism forever compromised by it. Some stayed behind in order to relive the best part of the war with girls, golf, and Singha beer at smoky saloons. Others were moved to atone for the war with charity -- educating Thai children, building hospitals for the Vietnamese, or providing medical care to Laotians they had befriended when soldiers. Whatever each mans motivation, the one attribute virtually all expat vets share is the desire to do what so many Americans dont want them to do: remember the Vietnam War.

Hard Men Humble brings a vivid cast of characters to life: Major Mark Smith, a much bemedaled winner of the Distinguished Service Cross and former prisoner of war who works out of Bangkok relentlessly searching for MIAs; Ken Richter, once a Jersey City tough, who discovered discipline and honor in Special Forces and who now donates much of his earnings to Southeast Asian charities; Robert Taylor, a former Green Beret from Alaska who formed a bond with a Lao tribe with which he worked, and who founded a medical charity for them; and Greg Kleven, an Oakland-born Force Recon marine who lost faith in the war and in his country, descended into dissoluteness and self-destructive drinking, and believes that moving to Ho Chi Minh City saved his life. The expatriate Vietnam veterans are, ultimately, just like any other cross section of Americans: some are heroes, a few are knaves, and others are just ordinary men trying to make a living. Ironically, the very dismissal of Vietnam veterans in the United States has driven some of them to build a life abroad of greater imagination, adventure, benevolence, and fulfillment than they might have found at home. Whether or not Americans doubt the wisdom of their larger historical mission, Vietnam veterans risked their lives to serve their country. We owe them our gratitude.