Galway Women in the Nineteenth Century » książka

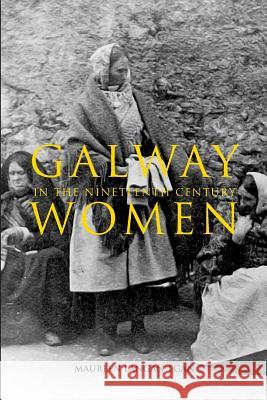

Galway Women in the Nineteenth Century

ISBN-13: 9781910388037 / Angielski / Miękka / 2014 / 180 str.

This book delineates the lives of the 'Unknown Irishwoman' in a turbulent century in Galway County and City on Ireland's western seaboard. Their (Irishwomen') lot in history cannot easily be measured. Much of it has disappeared; more of it was never recorded (Bowman, 2014). The work tells many of the untold or forgotten stories of 'the lives of women which slide between the cracks', to cite the novelist Martina Devlin (2014) and who could so easily be completely written out of history. The book will appeal to the local historian, those with an interest in social history, women's history and the general reader. The book is organised into three main sections, each of which has a number of chapters. They are The Necessities of Life, The Nature of Society and Distress, followed by an Epilogue and Addenda. The Necessities of Life include chapters on Employment, Housing, Clothing and Food 'always the major source of anxiety for the labourer of Ireland' (O'Neill, 1984). The Nature of Society deals with Marriage, Unmarried Mothers, Religion and Education. The double standards regarding sexual behaviour which pervaded society at the time are clearly shown. The section on Distress contains chapters on Distress and Famine, Migration and Emigration, Women and Crime. The different sentencing patterns in courts for both men and women are of interest. The Epilogue depicts reveals how women came to be more disadvantaged than in the earlier part of the century. The subservient role of women in Irish society was further emphasised when a new definition of work 'from being all work contributing to the operation of society to a narrower definition based on the idea of economic activity' introduced in the 1861 Census meant that many women became invisible, from an official point of view. From that point on, women's non-wage labour counted for nought in official records. This further lowered women's status in society (and was a huge contrast to the situation which pertained before 1815). Oxley (1996) argues that adherence to the notions of the market economy led to the undervaluing of women's contributions to an Irish society already divided along gender lines, where it was widely held that gender differences gave order, balance and rationality to human relations. While Bowman (2014) has stated that many women who emigrated were escaping the puritanical strain of Irish Catholicism, (which became widely prevalent with The Devotional Revolution, etc., see Chapter on Religion), it is important to remember that the attitude of the Churches in Ireland merely reinforced the current views of the Irish on society rather than initiated this point of view. The Epilogue also deals with the violence which underlay much of society and the attitudes of the courts to both male and female offenders. Male defendants were sometimes portrayed as victims in court and could be excused if their wives were inadequate housekeepers or homemakers, particularly if the women in question were fond of drink. Society demanded that women should be sober and compliant. The decades after the Great Famine present us with a picture of almost unrelenting gloom. There was widespread Famine in parts of the County in 1896-7, for instance. Conditions in Connemara were at their worst for several decades in 1924, as noted in the Dillon MS. Less obvious are the improvements in the lives of women which were hard won. At the beginning of the century, it could be stated that most Irish women experienced neither education nor emigration' (Fitzpatrick, 1986). The end of the century was conspicuous by their experience of both. Women used their education and the modern means of communication to further their interests. Through the Post Office, they became aware of opportunities overseas, knowledge of other lands, they used mail-order to good effect, they remitted money to family, mainly female, Ireland during the last century (Report of the Civil Service Competit