First Taken, Last Released: Overlooked WWII Internment » książka

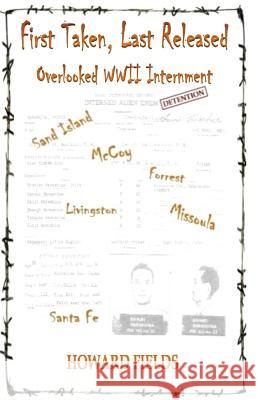

First Taken, Last Released: Overlooked WWII Internment

ISBN-13: 9781535409438 / Angielski / Miękka / 2016 / 252 str.

Most Americans whose family histories cover World War II are aware of the taciturn manner in which those of all cultures and nationalities who served or were imprisoned speak of what they experienced. It was as if an entire generation clammed up. Among those who did speak were a few who wrote the history that we have today of those times, just as journalists today are writing what will be the history that following generations will learn as history. It took years to get American veterans of that war to describe it, and only now are their exploits freely told. Similarly, people of Japanese ancestry forced from their homes in Hawaii and the US West Coast were loathe to talk about their incarceration. Eventually many did and we now have a lot of chronicles about life in what has become referred to in the Japanese community as American concentration camps. Many of those accounts were written by the children of internment, all with at least hyphenated citizenship who were penned up along with their parents. Many books on the subject list all of the camps where those interned families were kept. Those books and academic accounts, however, ignore at least half a dozen other camps where Japanese were held: Missoula in Montana, McCoy in Wisconsin, Forrest in Tennessee, Livingston in Louisiana and Santa Fe in New Mexico. Nearly all were located deeper into the interior of the US than the better known family camps of the Far West and even Hawaii. Most of the latter group were arrested under direction of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 issued on February 19, 1942. The numbers taken grew to more than 120,000 within weeks. Incarceration of Japanese actually began more than two months earlier, on December 7, 1941 before the smoke cleared over Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, nearly a day before the US declared war over the day that lived in infamy. The first 5,000 Japanese taken into custody were all men, the vast majority Issei born in Japan and no American citizenship, many intending to return to Japan. Along with them were Kibei sons born in the US with dual citizenship, but sent to Japan before the war to be raised in its culture and language in advance and returned. All 5,000 already had meticulous FBI dossiers, amassed over the previous several months as hostilities between Japan and the US heated up, expanding from words of recrimination to economic sanctions, reprisals and threats. The men drew the FBI's attention only because they were Issei, obviously loyal to their home country, but more importantly, they usually were community leaders or religious figures, language teachers or others considered to have influence in Japanese communities. That was particularly true in Hawaii where 40 percent of the population at the time was composed of pineapple and sugar cane workers of Japanese ancestry, many Issei themselves. Men at the top of the list were the first Japanese arrested even before martial law was declared at mid-afternoon of December 7. As the title suggests, the first-taken also became the last-released from behind barbed wire. For decades, knowledge of their experiences could be found only in two published books. The first was Life Behind Barbed Wire, by a Honolulu newspaper publisher, Yasutaro Soga, published in 1945 in Japanese and translated decades later into English. The second, which drew extensively from Soga's work, was Haisho Ten Ten, published in Japanese in 1964 by the Honolulu Japanese language newspaper Hawaii Times. As of this writing it was still being translated into English. The author was Kumaji Furuya, among the 160 first-taken and described his experiences as a prisoner held in places that save for one, were different from those where Soga was held. Furuya spent his entire time in the men-only internment camps in close proximity to Shinri Sarashina, one of the very first to be taken among the 160 as the No. 2 man in Hawaii of the predominant Buddhist sect. This is Shinri's sto

Zawartość książki może nie spełniać oczekiwań – reklamacje nie obejmują treści, która mogła nie być redakcyjnie ani merytorycznie opracowana.