District Six: Lest We Forget » książka

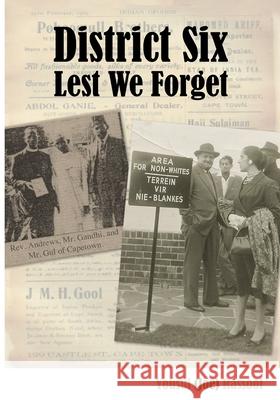

District Six: Lest We Forget

ISBN-13: 9781495295614 / Angielski / Miękka / 2014 / 192 str.

The context is Cape Town, South Africa of the 1930s as seen through the pre-teen eyes of the author, Yousuf 'Joe' Rassool when 'life was one interminable summer'. This family history covers the era of Gandhi in South Africa through the early Anti-Apartheid struggle. Rassool recalls characters of the time with a crystal clarity that is both the blessing and curse of those who went into exile. He brings to life No. 7 Buitencingle Street, the unoccupied and shuttered ancestral family home of the Gools that is opened to their relatives, the Rassools, as temporary accommodation. The house, now run down, spoke of a former grandeur, of lost nobility and wealth. It was once the venue of dignitaries, politicians, and intellectuals including Dr Abdulla Abdurahman, Henry Sylvester Williams, and MK Gandhi. Gool and several other associates including Dr. A. Abdurahman (who formed the African People's Organization), J. M. Wilson (Gool's African American accountant and business partner), Advocate Henry Sylvester Williams (who had called the first Pan African Congress and was the first black man to serve on the Cape Supreme Court) and J. W. Boyce became increasingly involved in the campaign to protest the erosion of the rights of non-whites, eventually leading to a strong political support of and friendship with Gandhi. Gool wrote to Gandhi in 1897. Gool and his associates shared the same belief that education was an essential weapon for their children to resists the assaults on their human rights. Their outlook transcended notions of race and was visionary even by today's standards. These visionaries were by no means revolutionaries - they did not propose the overthrow of the government nor Empire. Instead they simply wanted to claim their rights as subjects under the institution that they so revered. Abdul Hamid's return to the Cape in 1911 was in just in time to save No 7 Buitencingle from being sold and to arrest the declining family fortune. The house became the surgery and dispensary for his new medical practice. MK Gandhi, who had logged Abdul Hamid's educational progress in Indian Opinion, helped refurbish the front room by puttying and staining the wood floor. Gandhi often stayed at Buitencingle when he visited Cape Town. The Gools cared for Gandhi's frail wife, Kasturba. Abdul Hamid would hail Gandhi as 'Mahatma' in his farewell address in 1914. Friendship between the families brought together Abdul Hamid Gool, and Abdurahman's eldest daughter, Cissie. They were married in 1919. Cissie Gool became a legendary political force. Another Gool daughter, Gadija, married Advocate Christopher, one of Gandhi's lieutenants. Gool's association with Gandhi also led to a romance between Gool's daughter Timmie and Manilal, Gandhi's son. Gandhi eventually vetoed their marriage proposal citing the marriage between a Hindu and Muslim would be like 'putting two swords in one sheath.' Rassool continues, in Part Two of the book, to describe life in District Six in an era of great turbulence as the old colonial decay gave rise to the ghastly social experiment of Apartheid. He recalls characters of the time with a crystal clarity that is both the blessing and curse of those in exile. A world frozen in the time capsule of Joe's mind is exposed for a new generation to better understand their origins. His history is not a simpering glorification of the new order in post-Apartheid South Africa. Instead it covers the period during which the very nature of struggle and resistance was wrestled with in debating societies, schools, and cricket clubs. The struggle for a New South Africa that is revealed was not a linear, unified, coherent march of righteousness. It was, at times, egotistical, undisciplined, and destructive. Joe gives a fly-on-the-wall account of the key meetings of the Unity Movement, from the point of view of a young activist, and of its split whose fault-line ran right through the middle of his family.

Zawartość książki może nie spełniać oczekiwań – reklamacje nie obejmują treści, która mogła nie być redakcyjnie ani merytorycznie opracowana.