Dirt and Disease: Polio Before FDR » książka

topmenu

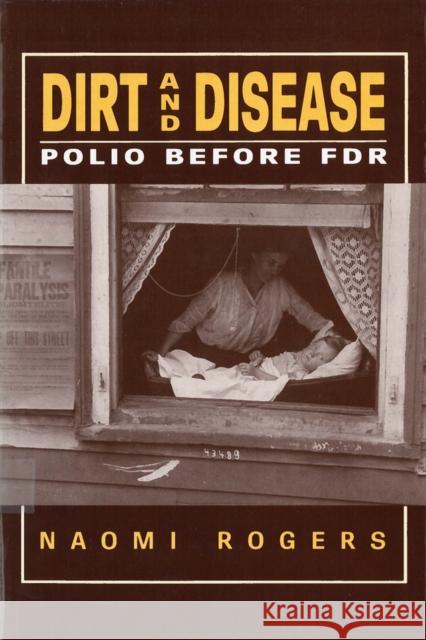

Dirt and Disease: Polio Before FDR

ISBN-13: 9780813517865 / Angielski / Miękka / 1992 / 258 str.

"Will have an enthusiastic audience among historians of medicine who are familiar, for the most part, only with later twentieth-century efforts to combat polio." --Allan M. Brandt, University of North Carolina

Dirt and Disease is a social, cultural, and medical history of the polio epidemic in the United States. Naomi Rogers focuses on the early years from 1900 to 1920, and continues the story to the present. She explores how scientists, physicians, patients, and their families explained the appearance and spread of polio and how they tried to cope with it. Rogers frames this study of polio within a set of larger questions about health and disease in twentieth-century American culture. In the early decades of this century, scientists sought to understand the nature of polio. They found that it was caused by a virus, and that it could often be diagnosed by analyzing spinal fluid. Although scientific information about polio was understood and accepted, it was not always definitive. This knowledge coexisted with traditional notions about disease and medicine. Polio struck wealthy and middle-class children as well as the poor. But experts and public health officials nonetheless blamed polio on a filthy urban environment, bad hygiene, and poverty. This allowed them to hold slum-dwelling immigrants responsible, and to believe that sanitary education and quarantines could lessen the spread of the disease. Even when experts acknowledged that polio struck the middle-class and native-born as well as immigrants, they tried to explain this away by blaming the fly for the spread of polio. Flies could land indiscriminately on the rich and the poor. In the 1930s, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt helped to recast the image of polio and to remove its stigma. No one could ignore the cross-spread of the disease. By the 1950s, the public was looking to science for prevention and therapy. But Rogers reminds us that the recent history of polio was more than the history of successful vaccines. She points to competing therapies, research tangents, and people who died from early vaccine trials.