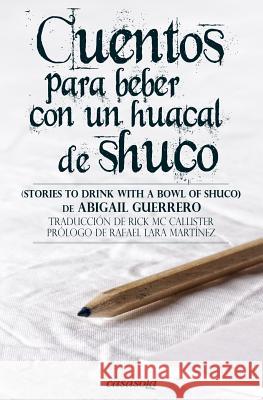

Cuentos para beber con un huacal de shuco » książka

Cuentos para beber con un huacal de shuco

ISBN-13: 9780988781269 / Angielski / Miękka / 2013 / 208 str.

Traduttore - tradittore say the Italians and "I plead guilty as charged." While I guarantee you will enjoy these stories in translation, I admit they can not live up to the originals. Every work of literature is an expression of the culture that produced it and presupposes a bit of insider knowledge. These stories are no exception. They all share references to shuco, which is consumed by millions of Salvadorans everyday and which is reputed to have miraculous qualities to raise the dead, or at least to abate hangovers. Shuco, or atol shuco, is a completely alien concept to the middle-class American palate. It is something between a hot beverage and a soup, similar perhaps to watery grits, oatmeal or mush with a punchy Central American flavor. Traditionally served in gourds made from morro fruit, it's more commonly dispensed in styrofoam cups on street corners for about a quarter ($0.25 US) by little old ladies who make just enough to survive on. Its ingredients include ground black corn, water, alguashte (al-WASH-teh) or ground pumpkin seed, cooked red beans and salt, to which chile or a shot of hot sauce is added. Served with pan frances (literally "French bread, but really dinner rolls), it makes a breakfast or lunch. The color of its ingredients gives it its name, for in Nawat Pipil, the ancestral language of much of El Salvador, tsukit means "mud," hence atol shuco is "muddy mush." You won't find shuco in any fancy restaurants or in the homes of the well-heeled, only on street corners or the most humble eateries, but it's an important part of life to the majority of people who work hard for a meager living and for whom it's an everyday treat, a hangover cure, an occasional luxury, a pick-me-up while waiting for the bus in the rain or the only thing one can afford that day. I promise not to spoil the stories with details because I trust that you the reader are intelligent enough to form your own conclusions but a few concepts are in order. A few of the stories rely on the concept of magical realism -the idea that eve- ryday life in Latin America transcends anything conceivable to those live in developed countries. Others are existentialist -the struggle for survival in a country with few opportunities for the many can lead to madness. The long hours, strenuous work, low pay, abusive supervisors and unbelievably high crime rate drives people to desperation. Yet people dream, hope and pray for escape from conditions those in wealthy countries can scarcely imagine. One means of escape is science fiction, which has become very popular only recently in the region. Any sci-fi movie from anywhere in the world can be found for a dollar at the pirate DVD sidewalk emporium on Calle Arce in downtown San Sal- vador. The impact of this genre is quite apparent in "Ciudad Nopticon / Nopticon City," whose title is inspired by Jeremy Bentham's famous 1785 prison design which included a built in all-seeing eye in the form of an inner tower to watch over the prisoners without being seen. That the French philosopher Michel Foucault helped build his career on this concept is germane, because his belief that knowledge/power was a formidable weapon in the hands of the ruling elite also informs this story. If your Spanish is limited or rusty, make an effort at reading the stories in the original language, you'll be glad you did. Salvadoran Spanish is basically the same Spanish you learned at school or heard your grandparents speak, but with a few local peculiarities such as vos, instead of tu for the familiar second person singular. The localisms are covered in a glossary, since they won't necessarily be understood by Spanish-speakers from other countries either. Most of them, and any other word you don't understand is explained (in Spanish) at the Real Academia Espanola website www.rae.es and in English at various on-line dictionary sites."