Andrea Dworkin » książka

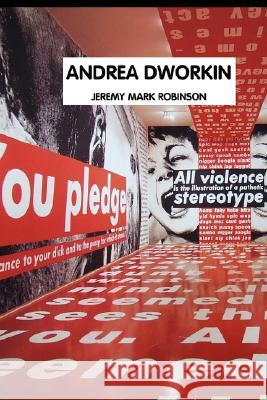

Andrea Dworkin

ISBN-13: 9781861711267 / Angielski / Miękka / 2008 / 196 str.

ANDREA DWORKIN Of this study of her work, Andrea Dworkin wrote: It's amazing for me to see my work treated with such passion and respect. There is nothing resembling it in the U.S. in relation to my work. Michael Moorcock wrote of American feminist and writer Andrea Dworkin: 'I think feminism is the most important political movement of our times. People think Andrea's a man-hater. She gets called a Fascist and a Nazi - particularly by the American left, but it's not detectable in her work. To me she seemed like a pussycat... She has an extraordinary eloquence, a kind of magic that moves people'. Dworkin is a very positive writer, always driving onwards for revolution, change and radical thinking. In the introduction to Letters From a War Zone, she writes: 'I am more reckless now than when I started out because I know what everything costs and it doesn't matter. I have paid a lot to write what I believe to be true. On one level, I suffer terribly from the disdain that much of my work has met. On another, deeper level, I don't give a fuck'. Dworkin's life's work balances the individual suffering of the writer with the larger, worldwide suffering of women's subordination, so that, she says, one becomes, on a personal level, immune to pain, while on the larger, global level, the pain of women and children around the world continues to grow, and continues to make her madder and madder: 'I wrote them essays and speeches] because I believe in writing, in its power to right wrongs, to change how people see and think, to change how and what people know, to change how and why people act. I wrote them out of the conviction, Quaker in origin, that one must speak truth to power. This is the basic premise in my work as a feminist: activism or writing'. Here Dworkin posits her work as a crusade, that's the newspaper term for her kind of polemic, a 'crusade' against silence and violence, against cruelty and inequality, and certainly Dworkin is often portrayed in the media as a crusader, someone who really believes in herself, in her convictions, someone wholly committed, as few others are, to a radical change. Michael Moorcock, in his piece on Andrea Dworkin (New Statesman, 1988) writes: w]hat she fights against, in everything she writes and does, is male refusal to acknowledge sexual inequality, male hatred of women, male contempt for women, male power'.

ANDREA DWORKIN

Of this study of her work, Andrea Dworkin wrote:

It’s amazing for me to see my work treated with such passion and respect. There is nothing resembling it in the U.S. in relation to my work.

Michael Moorcock wrote of American feminist and writer Andrea Dworkin: ‘I think feminism is the most important political movement of our times. People think Andrea’s a man-hater. She gets called a Fascist and a Nazi - particularly by the American left, but it’s not detectable in her work. To me she seemed like a pussycat… She has an extraordinary eloquence, a kind of magic that moves people’.

Dworkin is a very positive writer, always driving onwards for revolution, change and radical thinking. In the introduction to Letters From a War Zone, she writes: ‘I am more reckless now than when I started out because I know what everything costs and it doesn’t matter. I have paid a lot to write what I believe to be true. On one level, I suffer terribly from the disdain that much of my work has met. On another, deeper level, I don’t give a fuck’.

Dworkin’s life’s work balances the individual suffering of the writer with the larger, worldwide suffering of women’s subordination, so that, she says, one becomes, on a personal level, immune to pain, while on the larger, global level, the pain of women and children around the world continues to grow, and continues to make her madder and madder: ‘I wrote them [essays and speeches] because I believe in writing, in its power to right wrongs, to change how people see and think, to change how and what people know, to change how and why people act. I wrote them out of the conviction, Quaker in origin, that one must speak truth to power. This is the basic premise in my work as a feminist: activism or writing’. Here Dworkin posits her work as a crusade, that’s the newspaper term for her kind of polemic, a ‘crusade’ against silence and violence, against cruelty and inequality, and certainly Dworkin is often portrayed in the media as a crusader, someone who really believes in herself, in her convictions, someone wholly committed, as few others are, to a radical change. Michael Moorcock, in his piece on Andrea Dworkin (New Statesman, 1988) writes: [w]hat she fights against, in everything she writes and does, is male refusal to acknowledge sexual inequality, male hatred of women, male contempt for women, male power’.