The Hidden Freud: His Hassidic Roots » książka

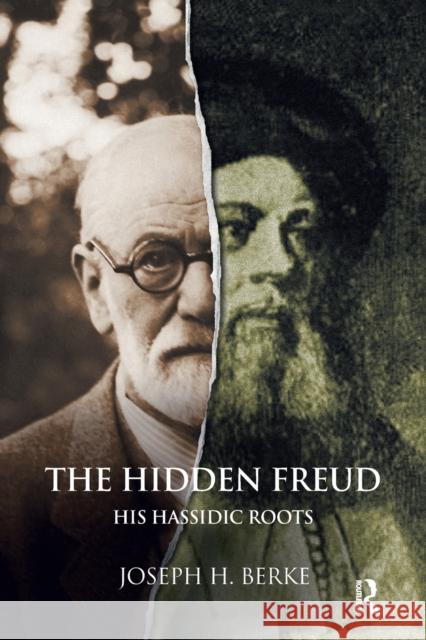

The Hidden Freud: His Hassidic Roots

ISBN-13: 9781780490311 / Angielski / Miękka / 2015 / 250 str.

The Hidden Freud: His Hassidic Roots

ISBN-13: 9781780490311 / Angielski / Miękka / 2015 / 250 str.

(netto: 174,30 VAT: 5%)

Najniższa cena z 30 dni: 169,28

ok. 16-18 dni roboczych.

Darmowa dostawa!

This book explores Sigmund Freud and his Jewish roots and demonstrates the input of the Jewish mystical tradition into Western culture via psychoanalysis. It shows in particular how the ideas of Kabbalah and Hassidism have profoundly influenced and enriched our understanding of mental processes and clinical practices.

Freud's own ancestors were Hassidic going back many generations, and the book examines how this background influenced both his life and his work. It also shows how he struggled to deny these roots in order to be accepted as a secular, German professional, and at the same time how he used them in the development of his ideas about dreaming, sexuality, depression and mental structures as well as healing practices. The book argues that in many important respects psychoanalysis can be seen as a secular extension of Kabbalah.

The author shows, for example, how Freud utilized the Jewish mystical tradition to develop a science of subjectivity. This involved the systematic exploration of human experience, uncovering the secret compartments and deepest levels of the mind (such as the preconscious and unconscious methods of thinking), expanding human consciousness beyond -objective- reality, and the revelation of hidden, unconscious thought processes by free association and dream analysis (all linked to kabbalistic modalities such as -skipping and jumping-). The book also explores the close connections between psychoanalysis, quantum physics, and Kabbalah.

The Hidden Freud: His Hassidic Roots also uses the meetings that took place in 1903 between Freud and the great hassidic leader, the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Rebbe Rashab, as a point of departure to consider Freud's Jewish identity. While Freud may have felt himself to be -completely estranged from the religion of his fathers- he still remained a man who -never repudiated his people, who felt that he was in his essential nature a Jew, and who had no desire to alter that nature-, as so many of his colleagues had done. Freud lived the life of a secular, skeptical Jewish intellectual. This was his revealed persona. But there was another, concealed Freud, who reveled in his meetings with the Rebbe, Kabbalists and Jewish scholars; who kept books on Jewish mysticism in his library; and who chose to die on Yom Kippur, 1939, the Day of Atonement. This book considers the implications of the -concealed Freud- on his life and work.