Thirty » książka

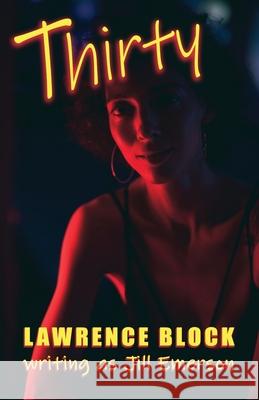

Thirty

ISBN-13: 9781539543558 / Angielski / Miękka / 2016 / 210 str.

THIRTY, as intensely erotic a book as I'd ever written, is what happened after I stopped writing erotica. Beginning with CARLA in 1958, I spent half a dozen years laboring in the vineyards of Midcentury Erotica, writing no end of books for Midwood, Nightstand, Beacon, et.al. It was a wonderful training ground, a comfortingly forgiving medium, and I've never regretted the timer I spent there, although for a time I wanted to disown the work I produced. (That changed with the passage of time, and now I've been eagerly reissuing much of that early work in my Collection of Classic Erotica. I like to tell myself this represents great progress in self-acceptance, but I have a hunch Ego and Avarice play a role here.) Never mind. I went on writing for Bill Hamling's Nightstand Books until a break with my agent deprived me of the market, andI can't regret that, either, because it's safe to say I'd stayed too long at the fair, and would have stayed longer still if given the chance. Instead, I took a job editing a numismatic magazine in Wisconsin and went on writing fiction in my free time. I placed some stories with Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine and THE GIRL WITH THE LONG GREEN HEART with Gold Medal, and then I wrote THE THIEF WHO COULDN'T SLEEP, which turned out to be the first of a series about a fellow named Evan Tanner. This was the first book in a voice that was uniquely mine, and the most satisfying work I'd ever done. I went on to write a total of seven books about Tanner (an eighth would follow after a 28-year interval) along with a couple of other crime novels, and then one day I got a call from my agent, Henry Morrison. Berkley Books wanted to launch a line of erotic novels, but on a different level from the old Midwood/Nightstand/Beacon ilk. It was 1968, censorship had essentially vanished, and American letters from top to bottom was embracing the sexual revolution and the new freedom. As Cole Porter might have put it, some authors who'd once been stuck with better words were now free to use four-letter words. Meanwhile, I was going through a period of discontent with the whole notion of fiction. I had nothing against the idea of making things up, but the artificiality of the novel suddenly rubbed me the wrong way. Narration, whether first person or third person, was a weird voice in one's ear. Who are you? Why are you telling me this? And why should I believe you? What appealed more were books that presented themselves as documents. Fictional diaries, fictional collections of letters, whatever. Yes, of course they were novels, we knew they were novels, but they took the form of actual documents. Thus THIRTY, which would take the form of a diary kept by a woman in her thirtieth year. I had just reached that age myself, and while I recognized it as a landmark, it seemed to me that turning thirty was rather a bigger deal for a woman than for a man, that it was very much a turning point. So I plunged in, and I strove throughout to write what Jan would have written in an actual diary, leaving things out, skipping days altogether, and letting characters come into and go out of her life, and events pile one on the other, the way they really do, with less pattern and logic than one typically demands of fiction. I just read the book prefatory to writing this book description, and I was surprised how much I liked it. (And how little of it I recalled.) I decided from the jump to put Jill Emerson's name on it, a name I'd shelved after WARM AND WILLING and ENOUGH OF SORROW. THIRTY is, to be sure, a creature of its time, as one knows when Jan whines about having to pay $375 a month for a Grove Street apartment. But I think the book holds up. In any event, Jill was back in business, and she'd go on to write two more books for Berkley's sexy new series, both of them pseudo-documents like THIRTY.

Zawartość książki może nie spełniać oczekiwań – reklamacje nie obejmują treści, która mogła nie być redakcyjnie ani merytorycznie opracowana.