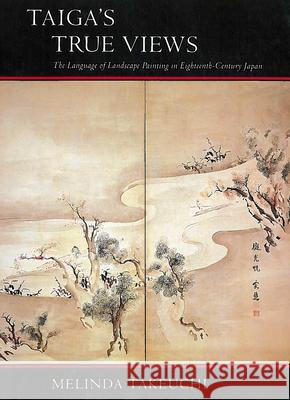

Taigaas True Views: The Language of Landscape Painting in Eighteenth-Century Japan » książka

Taigaas True Views: The Language of Landscape Painting in Eighteenth-Century Japan

ISBN-13: 9780804720885 / Angielski / Miękka / 1994 / 232 str.

In its broadest sense this book is about the relationship between topography and the language of visual symbols a painter manipulates, or must invent, to suggest specific places. How do artists communicate identifiable localities in paintings? What meanings are encoded in topographical paintings? What do such pictures tell us about artist, audience, and society? What do these paintings reveal about deeply felt cultural attitudes about place? This book is also about a central moment in Japanese painting. The middle decades of the eighteenth centruy were a time of enormous creative energy and burgeoning intellectual curiousity. A growing stress on the personality of the artist gave rise to a change in the staus of the painter, who came to be seen as someone whose expereinces were worthy of appreciation. Ike Taiga (1723-76), by virtue of his talent, foreceful personality, and sensitivity to his patrons' tastes, captured the energy and aspirations of his age. His career is emblematic of the changes in the intellectual order. He began as a humble artisan, producing on demand utilitarian items such as fans, decorated lanterns, seals, underdrawings for woodblocks, and designs for fabrics. At his death, he was one of the most celebrated painters in Japan. Drawn to the study of Chinese culture at an early age, Taiga set out to transform himself into a cultivated man along the lines of the Chines literatus, or wen-jen. In the process, he discovered the melange of Ming and Ch'ing painting styles transimtted to Japan under the rubric of Chinese scholars' painting. In addition, Taiga devoted himself to the literary pursuits - arts in the Chinese context - of calligraphy, poetry, tea ceremony, herbalism, dance, and antiquarianism. In emulation of the Chinese ideal of seeking knowledge through observation and study of nature, Taiga embarked on many journeys throughout Japan. These trips proved auspicious, for they gave rise to networks of pantronage, helped diffuse the new literati style (called Nanga or Bunjinga) throughout Japan, and yielded the subject matter that was to become the centerpiece of Taiga's art - actual scenery.