Three Uses of the Knife: On the Nature and Purpose of Drama » książka

topmenu

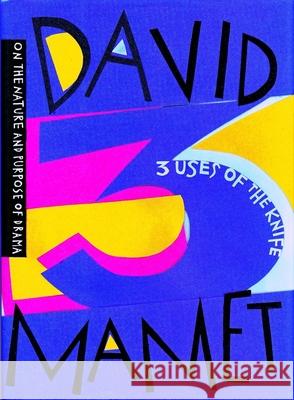

Three Uses of the Knife: On the Nature and Purpose of Drama

ISBN-13: 9780231110884 / Angielski / Twarda / 1998 / 96 str.

Three Uses of the Knife: On the Nature and Purpose of Drama

ISBN-13: 9780231110884 / Angielski / Twarda / 1998 / 96 str.

cena 133,31

(netto: 126,96 VAT: 5%)

Najniższa cena z 30 dni: 116,39

(netto: 126,96 VAT: 5%)

Najniższa cena z 30 dni: 116,39

Termin realizacji zamówienia:

ok. 16-18 dni roboczych.

ok. 16-18 dni roboczych.

Darmowa dostawa!

What makes good drama? How does drama matter in our lives? In Three Uses of the Knife, one of America's most respected writers reminds us of the secret powers of the play. Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, screenwriter, poet, essayist, and director, David Mamet celebrates the absolute necessity of drama--and the experience of great plays--in our lurching attempts to make sense of ourselves and our world.

In three tightly woven essays of characteristic force and resonance, Mamet speaks about the connection of art to life, language to power, imagination to survival, the public spectacle to the private script. It is our fundamental nature to dramatize everything. As Mamet says, "Our understanding of our life, of our drama.... resolves itself into thirds: Once Upon a Time.... Years Passed.... And Then One Day." We inhabit a drama of daily life--waiting for a bus, describing a day's work, facing decisions, making choices, finding meaning. The essays in the book are an eloquent reminder of how life is filled with the small scenes of tragedy and comedy that can be described only as drama. First-rate theater, Mamet writes, satisfies the human hunger for ordering the world into cause-effect-conclusion. A good play calls for the protagonist "To create, in front of us, on the stage, his or her own character, the strength to continue. It is her striving to understand, to correctly assess, to face her own character (in her choice of battles) that inspires us--and gives the drama power to cleanse and enrich our own character." Drama works, in the end, when it supplies the meaning and wholeness once offered by magic and religion--an embodied journey from lie to truth, arrogance to wisdom. Mamet also writes of bad theater; of what it takes to write a play, and the often impossibly difficult progression from act to act; the nature of soliloquy; the contentless drama and empty theatrics of politics and popular entertainment; the ubiquity of stage and literary conventions in the most ordinary of lives; and the uselessness, finally, of drama--or any art--as ideology or propaganda.